Historic wet winter brings talk of the new gold rush in the mother lode.

Uniondemocrat.com Guy McCarthy May 2, 2023

Gold hunters and people who cater to them have been talking for months about how this spring and summer could be a boom season for prospecting in creeks, streams, and rivers of the Mother Lode. Their reasoning is sound, given that significant winter storms packing atmospheric rivers of precipitation have already unleashed millions of gallons of erosive runoff, and the significant winter snowpack is just beginning to melt off to unleash more raging waters into watersheds downstream. Gold seekers hope all that runoff is scraping out a bounty of long buried, undiscovered placer gold fragments, washing riches downstream that anyone with patience for panning can gather on their own, or with the help of enterprising locals who cater to gold-mining tourism.

Jonathan Christian, 23, and his father, Dave Christian, 63, came from Manteca to try their luck Friday as paying clients at the business California Gold Panning next to Woods Creek in Jamestown. They’ve been fishing the South Fork Stanislaus River and Clarks Fork for nine years and have been talking about trying gold panning since 2020. “My wife suggested we try this out so we looked it up online,” Dave Christian said. “We’re here to celebrate Jonathan’s graduation in four weeks from San Joaquin Delta College in Stockton.” The Christians listened intently while their guide, James Holman, 44, explained how recent storms have eroded new features in Woods Creek, in some cases down to creek bed bedrock, and how there’s likely more placer gold in the creek now. Holman showed how to use water, digging tools, strainers called classifiers, and pans to sift through sediment and rock fragments to uncover flakes of color and bits of gold that can be sold for cash or kept as souvenirs.

“My goal today working with you guys is to move that boulder out of the creek,” Holman said. “No one’s ever moved it, so if there’s gold, it will be between there and the bedrock I’m standing on. We’ve pulled out probably two to three pennyweights in this section in the last day or two. A pennyweight’s 1.25 grams, worth about a hundred dollars, so it makes it worth it.” Holman also showed the Christians what he described as a perfect quartz specimen from the creek. The specimen contained quartz crystals, iron oxides, gold staining, and a visible fragment of trapped gold probably worth $10.

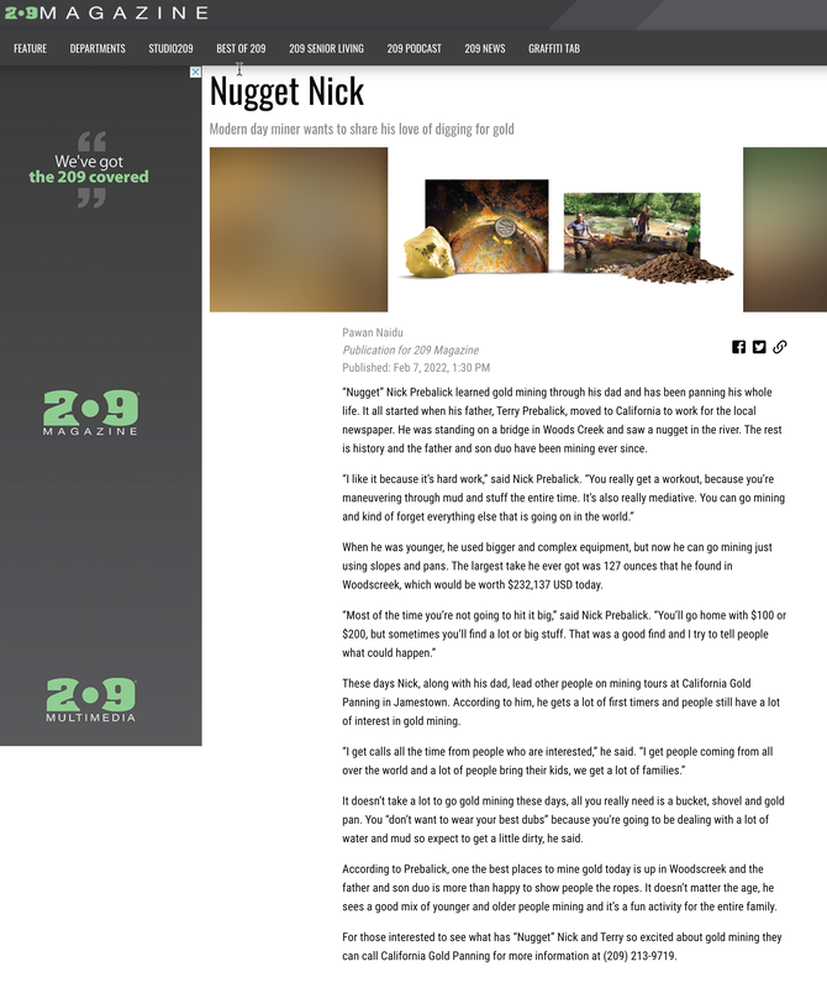

‘Nugget’ Nick

“Nugget” Nick Prebalick, 45, owner of California Gold Panning, said he knew this spring would be interesting and potentially more lucrative for gold seekers during the New Years Eve flood on Woods Creek. “It took out all the trees in the creek, made it a lot easier to get down in there, and it moved a lot of rock and overburden, all the topsoil,” said Prebalick, who’s been leasing land for his business for five years. “You could hear rocks and big boulders moving in the creek. That’s a good sign. It took part of my road, eroded that out, too, exposing more material.”

Prebalick likened the winter storms, runoff, and floods on Woods Creek so far this year to gravity-driven hydraulic mining with hoses that miners deployed once they built ditches and flumes to bring consistent water from higher in the Central Sierra to Columbia, Sonora, and Jamestown. “They used to strip down whole hillsides and hills to get to the gold fragments,” Prebalick said. “It clears out all the surface materials and loosens up the placer gold.” Prebalick said he has been prospecting gold in the Mother Lode all his life. He learned it from his father, who used to run a printer for The Union Democrat in the 1970s when the paper was still printed in downtown Sonora.

One day, Prebalick’s father was on lunch break and watching people panning in Sonora Creek where the old Wagon Wheel used to be, and one of the panners hollered and held up what he claimed was a gold nugget. “He quit working at the paper and started panning for gold for a living,” Prebalick said. “Back then we were allowed to dredge. We dredged here on Woods Creek, on the Merced River near Bagby when McClure Reservoir was low, and near old town Melones in the 1990s until dredging became illegal.” Prebalick brought out two vials containing gold fragments, dumped one of the vial’s contents into a rusty gold pan, and said it was about a quarter-ounce, worth about $500. Prebalick estimated he’s uncovered about 10 ounces of gold so far this year, worth an estimated $20,000. He said prospecting for gold and showing others how to do it is his job year-round.

California Gold Panning offers instruction, tools, tours, and digging parties to individuals, groups, families, and schools, as well corporate and team-building activities, Prebalick said, and he can take his show on the road as far as Los Angeles County and farther.

‘Miners would bring the gold to him’

It’s worth noting that Prebalick has already become a celebrity this spring, thanks to increased interest in gold hunting and the possibilities gold seekers may find in the wake of this winter’s runoff and erosion. “The only people who like big floods are gold miners,” Prebalick told the San Francisco Chronichle in February for a story headlined, “The surprising effect of California's storms on gold seekers.” Last Saturday, a similar story was published nationwide by The New York Times, and by Monday this week, Prebalick was on nationwide TV on Good Morning America.“I’ve had reporters left and right, Channel 3, Inside Edition, two interviews with ABC, a radio interview,” Prebalick said Friday. Holman said his family’s dog, Frankenstein, had dug up two gold nuggets in the past two days. Put together they weighed about a pennyweight, worth $100 or so. He introduced his daughter, Trinity, 11, who was minding a plastic sluice set up in the creek shallows to sift sediment and capture heavier gold fragments. “That’s our modern technology right there,” Holman said. “The same technology soldier miners used in the creek in Dragoon Gulch before they built the ditches and flumes. Miners back then had what they called long toms, wood sluices that could be 60 to 100 feet long. This one is the same as they used except it’s plastic.”

Holman said he believes John “Grizzly” Adams made more money off gold in Jamestown than anyone else because he had the mining supplies and he had the alcohol. A biographer and other historians concur that Adams came from Massachusetts through St. Louis to reach the California gold fields in 1849. The Jedediah Smith Society, named for the legendary mountain man who passed through the Central Sierra before the Gold Rush, recounts that Adams wintered on the upper Tuolumne River in 1853-54, then visited the valley named for its grizzlies, Yosemite. “He didn’t have to dig or sluice,” Holman said of Adams. “The miners would bring the gold to him.”

‘Backbreaking work’

Glen White, a geologist and earth sciences instructor at Columbia College, has lived on the side of Table Mountain on 49 acres outside Jamestown for more than four decades. There are two mines into the gravel under Table Mountain on White’s property. He understands how gold got here in the Mother Lode, and how it’s been eroded and moved around to various placer deposits. White agrees this past winter is “definitely in the top 10 of what I remember in terms of runoff and erosion” over the past 40 to 50 years. He lives on one side of Mormon Creek, which he has to cross each day to get home. “Our bridge goes under water during heavy rain events and we’ve had numerous events, but this wasn’t the highest water we’ve ever seen there,” White said. “The early 1980s was a big one. March 2005 was a pretty big one. What I noticed this winter at Mormon Creek, especially the big hail storm March 11, was the color of the creek. That was the fastest I’d seen Mormon Creek rise and the muddiest I’d ever seen it.”

White said he’s not a gold-mining enthusiast, and when his students ask him to look for gold he tells them “the jewelry store.” “It’s backbreaking work looking for gold,” White said. “It’s labor intensive. It’s a great opportunity to get outdoors, but I prefer to get outdoors and not do all the work.” Nevertheless, White said, this spring there is definitely the potential that gold has been mobilized in stream beds and possibly reburied. That doesn’t mean it’s going to be easy pickings, because nobody knows how much gold there was in the ground to start with, prior to the California Gold Rush.

“When you subtract what has been found during and since the Gold Rush, there’s just no way of knowing how much is left to be found,” White said. “And there’s no way of knowing how much of that remaining gold is placer gold, in other words the gold that’s been eroded out of hard rock, and we don’t know how much of that is still locked up underground in bedrock.”

There are a lot of unknowns for today’s gold seekers, White said. It’s great that people are interested and excited about it, but he urged people to remember to respect private property rights.

White said he’ll be leading a field trip for Sonora Elementary fourth graders and their teachers on the Columbia College campus next week, and it will feature geology, hydrology, and gold mining history on the campus, including the hydraulic mining in the Labyrinth area on the way to old town Columbia. "And of course we’re expecting questions from curious fourth graders about where the gold is,” White said. “If you could take all the gold that has been mined by humans around the world, it would form a perfect cube that’s 71 feet on each side. So remember the resource, gold, it’s finite and it’s rare.”

‘Rich experiences’

At the same time, some geologists think most of the gold in the Mother Lode is still in the ground, it hasn’t been found yet, and that’s an intriguing fact every year, regardless of how wet the winter season was, said Jeff Tolhurst, retired professor of geology at Columbia College.

Tolhurst, who specialized in rivers and hydrology and has lived in the Mother Lode since 1996, said Friday he used to teach a class called “geology and gold mining in Calaveras County.” “My buddy had up to seven gold mining claims, and we team-taught this class for about 10 years, in late spring and early summer each year,” Tolhurst said. “And we found gold in every single creek where we taught the class.” Nearly every student out of more than 100 over a decade “ found some color, meaning some kind of flakes to little tiny nuggets, the size of a rice krispie would the biggest,” Tolhurst said. “Most of them didn’t find rice krispies, they found flakes and they were yelling and screaming ‘woo hoo,’ “ he said. “It’s exciting when you see gold in your pan, even a little gold.”

So every stream probably has gold in it, and almost every person he taught found something, Tolhurst said. “But it’s not enough to get rich,” Tolhurst said. “We would spend one day studying geology and the second day was panning all day. It wasn’t a quarter-ounce or a half-ounce of gold each. It was a minuscule amount for a lot of backbreaking work.” When you look at the gold that’s been found in the Mother Lode since the Gold Rush, it’s mostly the river gold and the stream gold downstream from the Mother Lode faults, Tolhurst said. “But guess what? Most of the major faults are covered by reservoirs now,” Tolhurst said. “So people are going to have to wait until the reservoirs get low again to dig in the sediment, and that’s not happening right now. The reservoirs are full. Maybe next fall some of that sediment could get exposed.”

Tolhurst said in spite of conditions that can be interpreted as ideal for gold seekers this spring and summer, he thinks very few people are going to get rich, other than the people renting and selling mining equipment and renting out hotel rooms.

“They could get rich,” Tolhurst said. “And the tourists that come and do this, they will have rich experiences looking for gold because it’s so beautiful here. Being out on the river and panning, that’s fun. It’s a lot of work but students got a lot out of it. Living and working like miners, rough and ready, they enjoyed it, eating beef jerky, what a lifestyle. We worked them hard.”

Tolhurst’s students ended up sunburnt, mosquito-bitten, and sore. But they each had their little plastic vials of a tiny bit of gold. They had rich experiences and a little gold for the memory.

“That was one of the most enjoyable classes I taught before I retired, doing real geology, and they got to keep their gold,” Tolhurst said. “We taught them how gold forms in the Mother Lode, lode gold in the quartz veins that takes hard rock mining, and placer gold, the river and stream gold. It was real interesting and real fun.” State conservation authorities say that 195,000 troy ounces of gold valued at roughly $346 million were produced from 22 mines in California in 2020, a slight production increase from 2019. The Western Mesquite Mine, an open-pit heap-leach mine in Imperial County, led gold production with 141,270 ounces.

Contact Guy McCarthy at [email protected] or (209) 770-0405. Follow him on Twitter at @GuyMcCarthy.

Gold hunters and people who cater to them have been talking for months about how this spring and summer could be a boom season for prospecting in creeks, streams, and rivers of the Mother Lode. Their reasoning is sound, given that significant winter storms packing atmospheric rivers of precipitation have already unleashed millions of gallons of erosive runoff, and the significant winter snowpack is just beginning to melt off to unleash more raging waters into watersheds downstream. Gold seekers hope all that runoff is scraping out a bounty of long buried, undiscovered placer gold fragments, washing riches downstream that anyone with patience for panning can gather on their own, or with the help of enterprising locals who cater to gold-mining tourism.

Jonathan Christian, 23, and his father, Dave Christian, 63, came from Manteca to try their luck Friday as paying clients at the business California Gold Panning next to Woods Creek in Jamestown. They’ve been fishing the South Fork Stanislaus River and Clarks Fork for nine years and have been talking about trying gold panning since 2020. “My wife suggested we try this out so we looked it up online,” Dave Christian said. “We’re here to celebrate Jonathan’s graduation in four weeks from San Joaquin Delta College in Stockton.” The Christians listened intently while their guide, James Holman, 44, explained how recent storms have eroded new features in Woods Creek, in some cases down to creek bed bedrock, and how there’s likely more placer gold in the creek now. Holman showed how to use water, digging tools, strainers called classifiers, and pans to sift through sediment and rock fragments to uncover flakes of color and bits of gold that can be sold for cash or kept as souvenirs.

“My goal today working with you guys is to move that boulder out of the creek,” Holman said. “No one’s ever moved it, so if there’s gold, it will be between there and the bedrock I’m standing on. We’ve pulled out probably two to three pennyweights in this section in the last day or two. A pennyweight’s 1.25 grams, worth about a hundred dollars, so it makes it worth it.” Holman also showed the Christians what he described as a perfect quartz specimen from the creek. The specimen contained quartz crystals, iron oxides, gold staining, and a visible fragment of trapped gold probably worth $10.

‘Nugget’ Nick

“Nugget” Nick Prebalick, 45, owner of California Gold Panning, said he knew this spring would be interesting and potentially more lucrative for gold seekers during the New Years Eve flood on Woods Creek. “It took out all the trees in the creek, made it a lot easier to get down in there, and it moved a lot of rock and overburden, all the topsoil,” said Prebalick, who’s been leasing land for his business for five years. “You could hear rocks and big boulders moving in the creek. That’s a good sign. It took part of my road, eroded that out, too, exposing more material.”

Prebalick likened the winter storms, runoff, and floods on Woods Creek so far this year to gravity-driven hydraulic mining with hoses that miners deployed once they built ditches and flumes to bring consistent water from higher in the Central Sierra to Columbia, Sonora, and Jamestown. “They used to strip down whole hillsides and hills to get to the gold fragments,” Prebalick said. “It clears out all the surface materials and loosens up the placer gold.” Prebalick said he has been prospecting gold in the Mother Lode all his life. He learned it from his father, who used to run a printer for The Union Democrat in the 1970s when the paper was still printed in downtown Sonora.

One day, Prebalick’s father was on lunch break and watching people panning in Sonora Creek where the old Wagon Wheel used to be, and one of the panners hollered and held up what he claimed was a gold nugget. “He quit working at the paper and started panning for gold for a living,” Prebalick said. “Back then we were allowed to dredge. We dredged here on Woods Creek, on the Merced River near Bagby when McClure Reservoir was low, and near old town Melones in the 1990s until dredging became illegal.” Prebalick brought out two vials containing gold fragments, dumped one of the vial’s contents into a rusty gold pan, and said it was about a quarter-ounce, worth about $500. Prebalick estimated he’s uncovered about 10 ounces of gold so far this year, worth an estimated $20,000. He said prospecting for gold and showing others how to do it is his job year-round.

California Gold Panning offers instruction, tools, tours, and digging parties to individuals, groups, families, and schools, as well corporate and team-building activities, Prebalick said, and he can take his show on the road as far as Los Angeles County and farther.

‘Miners would bring the gold to him’

It’s worth noting that Prebalick has already become a celebrity this spring, thanks to increased interest in gold hunting and the possibilities gold seekers may find in the wake of this winter’s runoff and erosion. “The only people who like big floods are gold miners,” Prebalick told the San Francisco Chronichle in February for a story headlined, “The surprising effect of California's storms on gold seekers.” Last Saturday, a similar story was published nationwide by The New York Times, and by Monday this week, Prebalick was on nationwide TV on Good Morning America.“I’ve had reporters left and right, Channel 3, Inside Edition, two interviews with ABC, a radio interview,” Prebalick said Friday. Holman said his family’s dog, Frankenstein, had dug up two gold nuggets in the past two days. Put together they weighed about a pennyweight, worth $100 or so. He introduced his daughter, Trinity, 11, who was minding a plastic sluice set up in the creek shallows to sift sediment and capture heavier gold fragments. “That’s our modern technology right there,” Holman said. “The same technology soldier miners used in the creek in Dragoon Gulch before they built the ditches and flumes. Miners back then had what they called long toms, wood sluices that could be 60 to 100 feet long. This one is the same as they used except it’s plastic.”

Holman said he believes John “Grizzly” Adams made more money off gold in Jamestown than anyone else because he had the mining supplies and he had the alcohol. A biographer and other historians concur that Adams came from Massachusetts through St. Louis to reach the California gold fields in 1849. The Jedediah Smith Society, named for the legendary mountain man who passed through the Central Sierra before the Gold Rush, recounts that Adams wintered on the upper Tuolumne River in 1853-54, then visited the valley named for its grizzlies, Yosemite. “He didn’t have to dig or sluice,” Holman said of Adams. “The miners would bring the gold to him.”

‘Backbreaking work’

Glen White, a geologist and earth sciences instructor at Columbia College, has lived on the side of Table Mountain on 49 acres outside Jamestown for more than four decades. There are two mines into the gravel under Table Mountain on White’s property. He understands how gold got here in the Mother Lode, and how it’s been eroded and moved around to various placer deposits. White agrees this past winter is “definitely in the top 10 of what I remember in terms of runoff and erosion” over the past 40 to 50 years. He lives on one side of Mormon Creek, which he has to cross each day to get home. “Our bridge goes under water during heavy rain events and we’ve had numerous events, but this wasn’t the highest water we’ve ever seen there,” White said. “The early 1980s was a big one. March 2005 was a pretty big one. What I noticed this winter at Mormon Creek, especially the big hail storm March 11, was the color of the creek. That was the fastest I’d seen Mormon Creek rise and the muddiest I’d ever seen it.”

White said he’s not a gold-mining enthusiast, and when his students ask him to look for gold he tells them “the jewelry store.” “It’s backbreaking work looking for gold,” White said. “It’s labor intensive. It’s a great opportunity to get outdoors, but I prefer to get outdoors and not do all the work.” Nevertheless, White said, this spring there is definitely the potential that gold has been mobilized in stream beds and possibly reburied. That doesn’t mean it’s going to be easy pickings, because nobody knows how much gold there was in the ground to start with, prior to the California Gold Rush.

“When you subtract what has been found during and since the Gold Rush, there’s just no way of knowing how much is left to be found,” White said. “And there’s no way of knowing how much of that remaining gold is placer gold, in other words the gold that’s been eroded out of hard rock, and we don’t know how much of that is still locked up underground in bedrock.”

There are a lot of unknowns for today’s gold seekers, White said. It’s great that people are interested and excited about it, but he urged people to remember to respect private property rights.

White said he’ll be leading a field trip for Sonora Elementary fourth graders and their teachers on the Columbia College campus next week, and it will feature geology, hydrology, and gold mining history on the campus, including the hydraulic mining in the Labyrinth area on the way to old town Columbia. "And of course we’re expecting questions from curious fourth graders about where the gold is,” White said. “If you could take all the gold that has been mined by humans around the world, it would form a perfect cube that’s 71 feet on each side. So remember the resource, gold, it’s finite and it’s rare.”

‘Rich experiences’

At the same time, some geologists think most of the gold in the Mother Lode is still in the ground, it hasn’t been found yet, and that’s an intriguing fact every year, regardless of how wet the winter season was, said Jeff Tolhurst, retired professor of geology at Columbia College.

Tolhurst, who specialized in rivers and hydrology and has lived in the Mother Lode since 1996, said Friday he used to teach a class called “geology and gold mining in Calaveras County.” “My buddy had up to seven gold mining claims, and we team-taught this class for about 10 years, in late spring and early summer each year,” Tolhurst said. “And we found gold in every single creek where we taught the class.” Nearly every student out of more than 100 over a decade “ found some color, meaning some kind of flakes to little tiny nuggets, the size of a rice krispie would the biggest,” Tolhurst said. “Most of them didn’t find rice krispies, they found flakes and they were yelling and screaming ‘woo hoo,’ “ he said. “It’s exciting when you see gold in your pan, even a little gold.”

So every stream probably has gold in it, and almost every person he taught found something, Tolhurst said. “But it’s not enough to get rich,” Tolhurst said. “We would spend one day studying geology and the second day was panning all day. It wasn’t a quarter-ounce or a half-ounce of gold each. It was a minuscule amount for a lot of backbreaking work.” When you look at the gold that’s been found in the Mother Lode since the Gold Rush, it’s mostly the river gold and the stream gold downstream from the Mother Lode faults, Tolhurst said. “But guess what? Most of the major faults are covered by reservoirs now,” Tolhurst said. “So people are going to have to wait until the reservoirs get low again to dig in the sediment, and that’s not happening right now. The reservoirs are full. Maybe next fall some of that sediment could get exposed.”

Tolhurst said in spite of conditions that can be interpreted as ideal for gold seekers this spring and summer, he thinks very few people are going to get rich, other than the people renting and selling mining equipment and renting out hotel rooms.

“They could get rich,” Tolhurst said. “And the tourists that come and do this, they will have rich experiences looking for gold because it’s so beautiful here. Being out on the river and panning, that’s fun. It’s a lot of work but students got a lot out of it. Living and working like miners, rough and ready, they enjoyed it, eating beef jerky, what a lifestyle. We worked them hard.”

Tolhurst’s students ended up sunburnt, mosquito-bitten, and sore. But they each had their little plastic vials of a tiny bit of gold. They had rich experiences and a little gold for the memory.

“That was one of the most enjoyable classes I taught before I retired, doing real geology, and they got to keep their gold,” Tolhurst said. “We taught them how gold forms in the Mother Lode, lode gold in the quartz veins that takes hard rock mining, and placer gold, the river and stream gold. It was real interesting and real fun.” State conservation authorities say that 195,000 troy ounces of gold valued at roughly $346 million were produced from 22 mines in California in 2020, a slight production increase from 2019. The Western Mesquite Mine, an open-pit heap-leach mine in Imperial County, led gold production with 141,270 ounces.

Contact Guy McCarthy at [email protected] or (209) 770-0405. Follow him on Twitter at @GuyMcCarthy.

More than 150 years later the hunt for gold is still on in NorCal. Winter storms bring a new fever

11:58 AM PST FEB 8, 2023~JASON MARKS

SACRAMENTO, Calif. --The recent heavy rains in the Sacramento Valley created flooding in many of the streams and rivers. It also pushed gold from the mountains down into the valley, leading to a bit of a gold rush. Nestled along the south fork of the American River is a place where the name speaks for itself. Marshall Gold Discovery State Park in Coloma is a spot rich in history. The first nugget was discovered there in 1848. More than 150 years later, that fever is still being felt.

Ed Allen is the park's historian. He said he's "always looking" for gold. At 75 years old, he’s still giving tours to those who want to learn more about the gold rush. He’s amassed a wealth of knowledge when it comes to that precious metal so many continue to try and unearth. “We just had a flood here last month and that brought down gold," Allen said, sitting next to the American River. “People are still looking for gold. We've only found 10-15% of the gold in California."

At Wood's Creek in Jamestown, the hunt is on for that other 85%.

"This is the good stuff, and the best stuff will be in this box at the end of the day," Nick “Nugget” Prebalick said.

His family is leasing a 500-yard claim along the creek where they can search for gold. "I've found quite a few nuggets,” Prebalick said. Every day, Prebalick, his son Nate and his dad Terry are out prospecting. "It's pretty easy to get hooked,” Prebalick said. “This is like the best office ever." The family is using the same equipment used centuries ago. The only difference now is that metal pans have been replaced by plastic. The Prebalicks aren't just looking for pay dirt. They spend days running their business, California Gold Panning, which teaches people like 24-year-old Ashley Hardy how to pan.

"It's kind of a cool experience to do that they were doing back then," Hardy said. "I see a good 10 pieces in there right now."

There is a huge nugget of a difference between when the 49ers first got on the scene and now. The price of gold in 1850 was $20 an ounce. Nowadays one ounce is worth a little more than $1,900.

"After you've been digging all day, you fill up 10-20 buckets and then it all comes down to that pan to see what's in there," Prebalick said. State law doesn't allow miners to use big machinery, so fate is left up to good old-fashioned elbow grease.

"The more earth you move the more gold you'll probably get,” employee James Holman said. “If you don't move any earth, you don't get any gold." A successful day for Holman and the Prebalicks is a pennyweight of gold or 1.5 grams worth about $80. "They didn't get all the gold and we are still on it,” Holman added.

Most of that 85% left is deep under the earth's surface. Allen said it is too expensive to be dug up, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t gold out there. Several years ago, a miner found a six-pound nugget in Butte County.

SACRAMENTO, Calif. --The recent heavy rains in the Sacramento Valley created flooding in many of the streams and rivers. It also pushed gold from the mountains down into the valley, leading to a bit of a gold rush. Nestled along the south fork of the American River is a place where the name speaks for itself. Marshall Gold Discovery State Park in Coloma is a spot rich in history. The first nugget was discovered there in 1848. More than 150 years later, that fever is still being felt.

Ed Allen is the park's historian. He said he's "always looking" for gold. At 75 years old, he’s still giving tours to those who want to learn more about the gold rush. He’s amassed a wealth of knowledge when it comes to that precious metal so many continue to try and unearth. “We just had a flood here last month and that brought down gold," Allen said, sitting next to the American River. “People are still looking for gold. We've only found 10-15% of the gold in California."

At Wood's Creek in Jamestown, the hunt is on for that other 85%.

"This is the good stuff, and the best stuff will be in this box at the end of the day," Nick “Nugget” Prebalick said.

His family is leasing a 500-yard claim along the creek where they can search for gold. "I've found quite a few nuggets,” Prebalick said. Every day, Prebalick, his son Nate and his dad Terry are out prospecting. "It's pretty easy to get hooked,” Prebalick said. “This is like the best office ever." The family is using the same equipment used centuries ago. The only difference now is that metal pans have been replaced by plastic. The Prebalicks aren't just looking for pay dirt. They spend days running their business, California Gold Panning, which teaches people like 24-year-old Ashley Hardy how to pan.

"It's kind of a cool experience to do that they were doing back then," Hardy said. "I see a good 10 pieces in there right now."

There is a huge nugget of a difference between when the 49ers first got on the scene and now. The price of gold in 1850 was $20 an ounce. Nowadays one ounce is worth a little more than $1,900.

"After you've been digging all day, you fill up 10-20 buckets and then it all comes down to that pan to see what's in there," Prebalick said. State law doesn't allow miners to use big machinery, so fate is left up to good old-fashioned elbow grease.

"The more earth you move the more gold you'll probably get,” employee James Holman said. “If you don't move any earth, you don't get any gold." A successful day for Holman and the Prebalicks is a pennyweight of gold or 1.5 grams worth about $80. "They didn't get all the gold and we are still on it,” Holman added.

Most of that 85% left is deep under the earth's surface. Allen said it is too expensive to be dug up, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t gold out there. Several years ago, a miner found a six-pound nugget in Butte County.

NPR: Flooding was the downside to California's heavy rain. The upside: gold

May 2, 2023.

A MARTÍNEZ, HOST:

Floodwater in California has stirred up new deposits of gold in rivers and streams across the state. It's sparking what some are calling Gold Rush 2.0. OK, now, consider this - a lone figure, knee-deep in a creek, bent over a metal pan, sifting through dirt and gravel in search of gold. No, not a scene from the 1800s. It's California today during what some are calling gold rush 2.0.

ALBERT FAUSEL: Since our big rains this summer, the rivers and the creeks have really flooded and brought a lot of new material off the banks into the river, which has made kind of like a little gold rush going on here.

LEILA FADEL, HOST:

That's Albert Fausel. He owns a hardware store in Placerville and sells equipment for searching for precious metals.

FAUSEL: I've got people from New York coming over. I've got people from San Francisco just taking a day trip up here. People from even Idaho coming down here.

FADEL: These conditions for prospecting gold are like nothing Nick Prebalick has seen before.

NICK PREBALICK: What it used to be like - we'd have to dig for a lot longer just to get down to the gold. Right now, we're able to get down to where the gold is real easy without even digging hardly at all.

MARTÍNEZ: Prebalick's family has been gold mining for generations. He spoke to us while he was out at Wood's Creek, near Jamestown, Calif.

PREBALICK: You're looking at the creek right now. It's real peaceful, you know, just to hear the running water. You know, it's kind of meditative. At the same time, it is a lot like fishing. It's a mixture between fishing and playing a slot machine - you know? - 'cause you could hit some money just all of a sudden, too.

FADEL: Prebalick is known to his friends as Nugget Nick. He says he hits the jackpot a lot, as recently as last weekend.

PREBALICK: I found about $250 worth of gold. I was out here all day, but I might have done a couple hours' worth of digging the whole time. That's $125 an hour. That's a pretty good wage.

FADEL: Nugget Nick also teaches people to pan for gold, though he says it's not the way to get rich quick.

PREBALICK: The thing about doing it for a living is that if you don't find gold that day or enough that month, how are you going to pay all your bills? It's a much better hobby. If you're counting just on the gold to pay your bills, I wouldn't count on that.

MARTÍNEZ: Hardware store owner Albert Fausel agrees, but says some people do get lucky.

FAUSEL: I'd say you're joining a lot of people, and it's tough out there. It's not as easy as it looks. But some people do get lucky on their first try. And I think you could, you know, find that pocket of gold or you could hit that vein or you could even maybe hit some, you know, lost artifact, like a $20 gold piece that a miner dropped out of his pocket.

MARTÍNEZ: Hey, as long as I can turn that gold piece into a chain, it'd be worth it.

A MARTÍNEZ, HOST:

Floodwater in California has stirred up new deposits of gold in rivers and streams across the state. It's sparking what some are calling Gold Rush 2.0. OK, now, consider this - a lone figure, knee-deep in a creek, bent over a metal pan, sifting through dirt and gravel in search of gold. No, not a scene from the 1800s. It's California today during what some are calling gold rush 2.0.

ALBERT FAUSEL: Since our big rains this summer, the rivers and the creeks have really flooded and brought a lot of new material off the banks into the river, which has made kind of like a little gold rush going on here.

LEILA FADEL, HOST:

That's Albert Fausel. He owns a hardware store in Placerville and sells equipment for searching for precious metals.

FAUSEL: I've got people from New York coming over. I've got people from San Francisco just taking a day trip up here. People from even Idaho coming down here.

FADEL: These conditions for prospecting gold are like nothing Nick Prebalick has seen before.

NICK PREBALICK: What it used to be like - we'd have to dig for a lot longer just to get down to the gold. Right now, we're able to get down to where the gold is real easy without even digging hardly at all.

MARTÍNEZ: Prebalick's family has been gold mining for generations. He spoke to us while he was out at Wood's Creek, near Jamestown, Calif.

PREBALICK: You're looking at the creek right now. It's real peaceful, you know, just to hear the running water. You know, it's kind of meditative. At the same time, it is a lot like fishing. It's a mixture between fishing and playing a slot machine - you know? - 'cause you could hit some money just all of a sudden, too.

FADEL: Prebalick is known to his friends as Nugget Nick. He says he hits the jackpot a lot, as recently as last weekend.

PREBALICK: I found about $250 worth of gold. I was out here all day, but I might have done a couple hours' worth of digging the whole time. That's $125 an hour. That's a pretty good wage.

FADEL: Nugget Nick also teaches people to pan for gold, though he says it's not the way to get rich quick.

PREBALICK: The thing about doing it for a living is that if you don't find gold that day or enough that month, how are you going to pay all your bills? It's a much better hobby. If you're counting just on the gold to pay your bills, I wouldn't count on that.

MARTÍNEZ: Hardware store owner Albert Fausel agrees, but says some people do get lucky.

FAUSEL: I'd say you're joining a lot of people, and it's tough out there. It's not as easy as it looks. But some people do get lucky on their first try. And I think you could, you know, find that pocket of gold or you could hit that vein or you could even maybe hit some, you know, lost artifact, like a $20 gold piece that a miner dropped out of his pocket.

MARTÍNEZ: Hey, as long as I can turn that gold piece into a chain, it'd be worth it.

Additional Links that include our team and claim:

14 Places You Can Still Pan For Gold In California's Hills

Here are places in Northern CA where you can learn to pan for gold.

TripAdvisor CA Gold Panning

14 Places You Can Still Pan For Gold In California's Hills

Here are places in Northern CA where you can learn to pan for gold.

TripAdvisor CA Gold Panning

The surprising effect of California’s storms on gold seekers

January’s storms flushed new sediment down Sierra rivers — and some gold panners are reaping the benefits.

Claire Hao Feb. 11, 2023Updated: Feb. 21, 2023

Two yellow specks, each barely half the size of a pinky nail, stood out amid the rest of the river sediment in Terry Prebalick’s green pan. Gold — about $100 of it, he estimated. By the end of the hour, he had found another $200.

It was a sunny day in Jamestown (Tuolumne County), some of the best weather in a while, noted “Nugget” Nick Prebalick, Terry’s son. But the recent bad weather had also been a boon: The January storms had hastened mountain and river erosion, washing more than usual amounts of gold from hard-to-reach crannies under the earth into the Prebalick family’s corner of California.

“The only people who like big floods are gold miners,” family patriarch Terry Prebalick, who has been looking for gold since the 1970s, said with a chuckle. Ankle-deep in Woods Creek, grandpa, dad and son waded through with the same tools as the original Forty-Niners — many of them plastic instead of tin or iron — scooping dirt into buckets, shoveling sediment over sluice boxes and searching for the precious metal. Nate Prebalick, Nick’s son and Terry’s grandson, lifted his pan, showing off specks of gold that looked like a hearty sprinkling of ground pepper flakes. It was about four to five times the amount he usually finds, Nate said.

The storms did “months of work” for the family, ripping open channels of dirt along the creek that the three would’ve otherwise had to dig, Nick Prebalick said. Nate Prebalick pointed to a crevice that he was excavating. The rust and layers of clay atop the bedrock meant that humans hadn’t touched this bit of earth in a long time, if ever — all the better for his chances of finding gold, Nate said.

Gold is the heaviest material in the river, Nate Prebalick said, about 19 times denser than water. The Prebalicks use this and gravity to their advantage, gradually sifting lighter material out of the pan until only gold and other heavy sediments are left. The team also shovels dirt into a sluice box to speed up the process: using the natural rush of the creek to sift the lighter material off the top, as gold sinks to the ridges along the bottom.

Some big mining companies took it up after the initial Forty-Niners with their gold pans, but heavy-duty hydraulic mining — a method of blasting high-pressure water onto a cliff face to wash away chunks of rock in the hopes of finding gold — was banned in the Sierra Nevada in 1884. Interest in panning for gold in rivers dropped until the Great Depression, according to Gold Rush historian Gage McKinney. During the Depression, California sponsored classes to train amateurs on how to make a living panning for gold, with classes taught at the Ferry Building, McKinney said. Gold mines started closing as the economy shifted to World War II wartime production, and as inflation made gold less profitable in the late 1940s and 1950s, McKinney said.

The Gold Rush means something a little different to every generation of Californians, McKinney said.

“For a long time, it was the story of the pioneers making new homes and making a new industrial state in California,” McKinney said. “More recently, people look back at the Gold Rush as a nightmare. It’s a nightmare of environmental degradation and abuse of indigenous people and exploitation of workers.” Interest in finding gold continues, despite the myriad environmental and human concerns that have accompanied the search over the years, starting with mercury contamination, the mistreatment of Chinese workers and violence toward and dispossession of Indigenous peoples during the original Gold Rush. Today, approximately 47,000 mines remain abandoned across the state, with concerns of degraded water quality for nearby localities.

“It's not possible to say how much gold is still left in California,” Don Drysdale, a spokesperson with the California Department of Conservation, said in an email. “The state’s geology is too complex. However, there is enough gold remaining that commercial mines are actively producing it.”

That includes in Grass Valley, where McKinney and his family live. Nevada-based Rise Gold Corp. is trying to reopen the Idaho-Maryland Mine in Grass Valley, though many residents are opposed, fearing negative environmental impacts. “If you drive around my neighborhood, you see yard signs all over the place that say ‘No mine,’ ” McKinney said.

Jarryd Gonzales, a spokesperson for the mining company, said that reopening the mine “has always been about more than creating hundreds of good-paying jobs, increasing fire safety, and boosting the local economy — it is about building an environmentally conscious state-of-the-art mine worthy of its community.”

Meanwhile at Woods Creek, most of the California Gold Panning team packed up around mid-afternoon, satisfied with their findings for the day. “The other guys are up here complaining that you got the most amount of gold for the least amount of work,” Terry’s wife ribbed.

Claire Hao Feb. 11, 2023Updated: Feb. 21, 2023

Two yellow specks, each barely half the size of a pinky nail, stood out amid the rest of the river sediment in Terry Prebalick’s green pan. Gold — about $100 of it, he estimated. By the end of the hour, he had found another $200.

It was a sunny day in Jamestown (Tuolumne County), some of the best weather in a while, noted “Nugget” Nick Prebalick, Terry’s son. But the recent bad weather had also been a boon: The January storms had hastened mountain and river erosion, washing more than usual amounts of gold from hard-to-reach crannies under the earth into the Prebalick family’s corner of California.

“The only people who like big floods are gold miners,” family patriarch Terry Prebalick, who has been looking for gold since the 1970s, said with a chuckle. Ankle-deep in Woods Creek, grandpa, dad and son waded through with the same tools as the original Forty-Niners — many of them plastic instead of tin or iron — scooping dirt into buckets, shoveling sediment over sluice boxes and searching for the precious metal. Nate Prebalick, Nick’s son and Terry’s grandson, lifted his pan, showing off specks of gold that looked like a hearty sprinkling of ground pepper flakes. It was about four to five times the amount he usually finds, Nate said.

The storms did “months of work” for the family, ripping open channels of dirt along the creek that the three would’ve otherwise had to dig, Nick Prebalick said. Nate Prebalick pointed to a crevice that he was excavating. The rust and layers of clay atop the bedrock meant that humans hadn’t touched this bit of earth in a long time, if ever — all the better for his chances of finding gold, Nate said.

Gold is the heaviest material in the river, Nate Prebalick said, about 19 times denser than water. The Prebalicks use this and gravity to their advantage, gradually sifting lighter material out of the pan until only gold and other heavy sediments are left. The team also shovels dirt into a sluice box to speed up the process: using the natural rush of the creek to sift the lighter material off the top, as gold sinks to the ridges along the bottom.

Some big mining companies took it up after the initial Forty-Niners with their gold pans, but heavy-duty hydraulic mining — a method of blasting high-pressure water onto a cliff face to wash away chunks of rock in the hopes of finding gold — was banned in the Sierra Nevada in 1884. Interest in panning for gold in rivers dropped until the Great Depression, according to Gold Rush historian Gage McKinney. During the Depression, California sponsored classes to train amateurs on how to make a living panning for gold, with classes taught at the Ferry Building, McKinney said. Gold mines started closing as the economy shifted to World War II wartime production, and as inflation made gold less profitable in the late 1940s and 1950s, McKinney said.

The Gold Rush means something a little different to every generation of Californians, McKinney said.

“For a long time, it was the story of the pioneers making new homes and making a new industrial state in California,” McKinney said. “More recently, people look back at the Gold Rush as a nightmare. It’s a nightmare of environmental degradation and abuse of indigenous people and exploitation of workers.” Interest in finding gold continues, despite the myriad environmental and human concerns that have accompanied the search over the years, starting with mercury contamination, the mistreatment of Chinese workers and violence toward and dispossession of Indigenous peoples during the original Gold Rush. Today, approximately 47,000 mines remain abandoned across the state, with concerns of degraded water quality for nearby localities.

“It's not possible to say how much gold is still left in California,” Don Drysdale, a spokesperson with the California Department of Conservation, said in an email. “The state’s geology is too complex. However, there is enough gold remaining that commercial mines are actively producing it.”

That includes in Grass Valley, where McKinney and his family live. Nevada-based Rise Gold Corp. is trying to reopen the Idaho-Maryland Mine in Grass Valley, though many residents are opposed, fearing negative environmental impacts. “If you drive around my neighborhood, you see yard signs all over the place that say ‘No mine,’ ” McKinney said.

Jarryd Gonzales, a spokesperson for the mining company, said that reopening the mine “has always been about more than creating hundreds of good-paying jobs, increasing fire safety, and boosting the local economy — it is about building an environmentally conscious state-of-the-art mine worthy of its community.”

Meanwhile at Woods Creek, most of the California Gold Panning team packed up around mid-afternoon, satisfied with their findings for the day. “The other guys are up here complaining that you got the most amount of gold for the least amount of work,” Terry’s wife ribbed.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.